“Disinterested interest” and the law of imagination: How can we encourage people to approach works of art with an open mind?

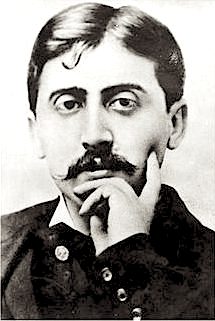

Like the memory of a faintly recalled melody whose origin one cannot quite place, I’ve recently found myself engaged in what could be described as an intellectual pas de deux of sorts—one where the ephemeral dance partners are concepts that I originally encountered through the works of two seminal, thought-provoking writers: Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) and Marcel Proust (1871–1922). Certain ideas central to the aesthetic precepts of this unlikely duo have led me to question whether common business practices we now take for granted, like the ubiquity of promotion and hype (both personal and professional), are an impediment to having an aesthetic experience. Or whether the constant bombardment of hype that we are all routinely subjected to is an inevitable byproduct of the over-connected, instantaneous access anywhere, anytime, fear of being ignored or worse—left out, times in which we live, and as such, is merely the justifiable price of a progress that will leave any behind who fail to get with the program and go with the flow, no matter where it takes us?

Perhaps I should give a brief description of the two concepts I’m referencing before I attempt to connect them and illustrate their collective salience to the issues I’m alluding to: namely, the detrimental effects of creating expectations (good or bad) for art intended to engender an aesthetic experience, especially in an age of oversaturation, where artists are trying to stand out in the crowd by any means necessary.

In his Critique of Judgement, philosopher Immanuel Kant addresses his ideas on judgement, including aesthetic judgement, which involves what he calls reflective judgement. Among the things that he says are required to have an aesthetic experience is what he calls a “disinterested interest.” Notice that he does not call it an “indifferent” or “uninterested” interest. Nevertheless, the term “disinterested interest” still gives one pause. What the hell is Kant talking about? I will flesh this concept out a bit later. But before I do so, I want at least to name the second partner in my mental dance, a concept that I first encountered in Marcel Proust’s masterpiece À la recherche du temps perdu, known in English as In Search of Lost Time. This concept is (for lack of a better term) called by Proust’s protagonist/narrator “the law of imagination”: i.e., you are forbidden from imagining what you see in front of you. Or as I see/hear it: if you are burdened with expectations about what you are seeing, hearing or reading, those expectations (good or bad) can and often do impede your ability to focus on the main event. But more about Proust’s masterful illustration of this a bit later, first I’ll attempt an explanation of Kant’s “disinterested interest.”

For Kant there are really only two categories of aesthetic experience: “the beautiful” and “the sublime.” If a work of art is to function as a conduit to an aesthetic experience, the audience must come to the work with a “disinterested interest.” So if one wants to have an aesthetic experience, ideally “one does not [or should not] have a personal self-interest in the work.” And hopefully one does not have any overriding preconceptions about the work either.

For example, it’s pretty easy to see how speculating on the potential increase in the value of a painting by an up-and-coming artist could impede the work from engendering an aesthetic experience, especially for one whose attention is focused solely on estimating future profits from resale when viewing the work. My philosophy teacher in college, Bernard Flynn, used to illustrate how self-interest can skew our perceptions by saying that, under the right circumstances (for example, if you are hungry enough), a ham sandwich is more interesting than a Mozart string quartet.

Most of us have had the experience of being told that something is dreadful with no firsthand knowledge of the book, film or recording referred to, and consequently deciding not to invest any time to discover whether the opinion we received is correct or not. Just as, conversely, we’ve all been told something is so great that we have to see, hear or read it, only to encounter the recommended work with such elevated expectations that we cannot really just be there and be open to what the work actually is, without comparing it to what we expected it would be. In simplified form this is my take on what Kant means by a “disinterested interest.” But Proust actually illustrates the concept in a thread that runs as a subplot in the first three volumes of In Search of Lost Time.

In Swann’s Way, volume 1 of In Search of Lost Time, we find Proust’s young narrator/protagonist (also named Marcel) dreaming of going to the theater to see Berma, the actress he has heard is the greatest living tragedienne (and who was based upon Sarah Bernhardt), perform the title role in Racine’s Phèdre. Marcel’s parents believe him too young to attend the theater, but in volume II, Within a Budding Grove, when his parents finally and unexpectedly relent, and he eagerly gets his wish, he is strangely disappointed during and after the performance. Berma simply is not all he had expected her to be. Of course, no one could have lived up to young Marcel’s inflated expectations, fueled by his anticipation of realizing a dream so long denied by his concerned parents.

In his mid-twenties Marcel finds himself at the theatre again for entirely different reasons, no longer expecting a life-altering performance. He now wants to see and be seen, in the hope of entering the social milieu of one Duchesse de Guermantes, who is now the prime focus of his expectations. So when Berma takes the stage, his experience is entirely different from previous occasions (from volume III: The Guermantes Way):

“And then, miraculously, like those lessons which we have laboured in vain to learn overnight and find intact, got by heart, on waking up next morning, and like those faces of dead friends which the impassioned efforts of our memory pursue without recapturing and which, when we are no longer thinking of them, are there before our eyes just as they were in life, the talent of Berma, which had evaded me when I sought so greedily to grasp its essence, now, after these years of oblivion, in this hour of indifference, imposed itself on my admiration with the force of self-evidence. . . .

My impression, to tell the truth, though more agreeable than on the earlier occasion, was not really different. Only, I no longer confronted it with a pre-existent, abstract and false idea of dramatic genius, and I understood now that dramatic genius was precisely this. It had just occurred to me that if I had not derived any pleasure from my first encounter with Berma, it was because, as earlier still when I used to meet Gilberte [who was Marcel’s first love] in the Champs-Elysées, I had come to her with too strong a desire.”

Proust’s observations are the best illustrations of Kant’s “disinterested interest” that I have ever encountered. They speak so clearly for themselves that I won’t insult anyone’s intelligence by attempting further explanation.

This now brings me to the related issues that prompted my recurring intellectual pas de deux in the first place. I’ll address them in the form of a rhetorical question (or two) intended hopefully to stimulate a conversation. While no one would want every aficionado, fan, friend, colleague or follower to be completely unaware of what we are attempting as artists (after all, folks rarely go out to hear music performed by artists they’ve heard or know nothing about), should we not be more aware that our promotion sets up expectations we are then somewhat obligated to fulfill, and shouldn’t we consider the unforeseen consequences that this hype routinely incurs in our social media, over-connected world? Like many an audience member and even some musicians who come to encounters with art without a “disinterested interest,” it seems to me that some critics make little or no effort whatsoever to leave their predetermined agendas at the door when critiquing the works created by artists aiming at targets these critics fail to recognize (to paraphrase Duke Ellington). Whatever genre of music one plays, we have all been confronted by colleagues and critics alike that self-righteously enforce a strict adherence to their interpretation of an agenda that they profess others follow. Be it the Bebop police, the Jazz police, the Swing police, the Samba police, the Clave police, the Blues police, the Funk police, the Rock police or whatever, they not only believe they alone know the “correct” version of “it,” but they will call out anyone not adhering to the gospel as they interpret it. So in our time-constrained, interconnected world, perhaps it is time to reconsider the advice of Kant and Proust. Perhaps we’d all be better off if we were to smell the flowers without predetermining what each flower should smell like before we even get within olfactory range.

Quotations are from Marcel Proust, In Search of Lost Time. Vol. III. The Guermantes Way, translated by C.K. Scott Moncrieff and Terence Kilmartin, revised by D. J. Enright, New York: Modern Library, 1993, pp. 54, 56