Jimi Hendrix and the Sound of Change

Is it some peculiar quirk of our relationship with time, or perhaps the innate need to find meaning in the confluence of seemingly unrelated events, that leads us to view life altering events as inevitable when considered in retrospect? I ask because this year the 4th of April marked the 45th anniversary of a day that irrevocably changed America, as well as the day that changed the course of my life in ways that now seem inevitable to me.

In 1968, April 4th occurred on a Thursday, just like it did this year. It was a day of great anticipation for me because, despite it being a school day, that evening I was going to hear Jimi Hendrix at the Alan B. Shepard Civic Auditorium (one of Buckminster Fuller’s Geodesic Domes, named for an astronaut and known to all the locals as the Virginia Beach Dome). I was fifteen years old and beginning to feel that music in general, and the guitar in particular, were the center of my life. So the chance to check out a live performance by the person who exemplified the upheavals afoot for both my instrument and the larger culture was irresistible (not that I even began to comprehend what these changes signified yet).

The burning of draft cards, forced bussing, desegregation, destruction of the inner cities, the proliferation of recreational drugs—both hard and hallucinogenic, sexual freedom and the women’s liberation movements were all on a horizon just beyond my adolescent view. Yet even in the relatively carefree, comfortable, middle class, rural/suburban environment in which I was growing up, we could sense the winds of change. The evening news made it clear that a lot of people were very unhappy with the status quo. In school we could feel an undercurrent of discontent, but I was not really sure why it was bubbling to the surface at that time. Like most teenagers, my world revolved around “ME” and my interests, and I was most interested in the guitar. So what attracted me to Jimi Hendrix was his guitar playing! His flamboyant clothes and wild behavior, like setting his guitar on fire or smashing his gear, were of little interest to me. His guitar sounded enormous, like a force of nature. Of course I’d only heard his recordings, but even there you got a clear sense that something new and excitingly different was happening. So for me it was his sound that I had to experience live, in part to see if I could figure out how on earth he created those otherworldly sounds.

For those of you familiar with my music, Jimi Hendrix must seem like the last possible influence detectable in my work. But at 15 he was for me what Wes Montgomery would later become, in other words, the standard of excellence to strive for. To say that the naïve expectations of a teenager from a southern rural/suburban Navy town during the height of the Vietnam War woefully underestimated what that evening held in store seems like the understatement of my life. I was too young even to drive myself to the concert, so my dad drove me from our home in Norfolk to the Dome in Virginia Beach, a few blocks from the Atlantic Ocean, and picked me up after the concert. Leaving the safe familiarity of his pickup truck, meandering through the crowds of long haired, colorfully clad hippies that were for the most part older than me, and entering the Dome, I gleaned my first clues that I was about to enter the rabbit hole. Once inside, the abundance of funny little rolled up things being smoked and liquid libations of every sort being imbibed, combined with activities deemed illegal in the state of Virginia added to the otherworldliness of the scene.

When the opening act “Soft Machine” (named after a William Burroughs book and led by keyboard player Mike Ratledge) took the stage, replete with a background light show, I knew I wasn’t in Kansas anymore. So I held on for the ride. The sounds, textures, harmonies and rhythms of their performance constituted what was for me a heretofore unexperienced level of interplay between musicians, and absolutely fascinated me. Time stood still and before I knew it, Soft Machine’s set was over.

The stage crew then began moving into place or somehow revealing (I’m still not sure how the gear got switched) the largest amplifiers I had ever seen. Being only familiar with Fender Twin and Super Reverbs as examples of big amps at that time, a Marshall Stack seemed enormous, and there were several of them occupying the left side of the stage! Before I knew what hit me, a guitar trio that I physically felt—like the winds of the hurricanes we grew up fearing in coastal Virginia and North Carolina—pinned me to my seat! Jimi and cohorts Noel Redding on bass and Mitch Mitchell on drums proceeded to turn my musical world upside down in such a manner that I actually felt I was living the Yardbirds’ “Over Under Sideways Down.” After breathtaking renditions of the now familiar classics like “Foxy Lady,” “Purple Haze,” “Wild Thing,” “The Wind Cries Mary,” “Manic Depression,” “Fire” and “Hey Joe,” performed totally differently from the recordings, it all ended far too soon. Yet despite Jimi’s mystifying reluctance to comply with the audience’s exuberant demands for encores, I felt I was beginning to understand why they called it the “Jimi Hendrix Experience,” because it was so different from any musical event I’d previously attended that it simply could not be described, or even talked about, really. It was as if any attempt to describe the experience diminished it in some way that made you feel like Judas. Only those privy to the event could understand.

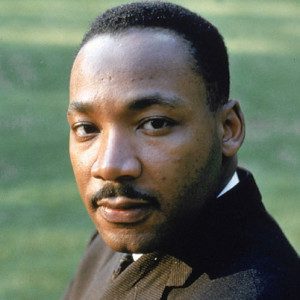

Wandering through the parking lot looking for my dad’s red pickup after the concert, I noticed people crying. Wow, were they that moved by what we had all just witnessed? I was knocked out all right, but not moved to tears; in awe yes, almost like I was floating blissfully above the realm of emotions. That is until I stepped into my dad’s truck, when I found out why there was no encore, and why folks in the parking lot were crying. In an era before smart phones, news traveled considerably slower than today . . . even news as horrible as what I learned upon closing the passenger door of my dad’s truck. Martin Luther King had been assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee, while I was having my musical DNA genetically altered as if by exposure to sonic radiation. In an instant I knew what the winds of change would bring, and why such change was unavoidably, inevitably, necessary. In a world sick enough to sacrifice one who advocated both the justice for all upon which our founding fathers built our nation, and the nonviolent means of redressing the promises left unfulfilled despite being categorically stated or implied in the very documents created to establish our nation’s most fundamental principles, I knew that only a metamorphosis like the overwhelmingly radical transformation from what was into what could be that I witnessed that night could possibly shake us from the lethargy of the self-interested status quo maintained by those controlling a system from which they profited disproportionately.

And so in reflecting upon the 45th anniversary of events both personal and universal, which changed our world individually and collectively in so many ways, it all seems so inevitable in retrospect, and I wonder if our current brand of injustice will also someday hear the winds of change approaching, and if so, what will that change sound like? Or are the odds just stacked too high for the genie ever to escape the bottle again? With multinational corporations beholden to no one, manipulating the levers of power in the sole pursuit of their own self interested agendas to the exclusion of any mitigating concerns for or responsibility to the planet, countries, or communities they too share, or to their workers or even the customers they rely on . . . with our elected officials feeding at the trough of corporate campaign contributions intended to keep the elite in power, and a revolving door of lobbyists to remind congress what side their bread is buttered on so that the continuance of the quid pro quo of corporate welfare can be insured for another generation . . . when we ourselves are bamboozled by the very ads purchased with these corporate payoffs—who do we turn to for change? In my youth it was to the sound of something as radical as Jimi Hendrix. But now we even hear his music in commercials. So I ask, what will change sound like in a future where music is ubiquitous? Will we even recognize it? And if we do, will it seem as inevitable decades after its occurrence as the sounds from 45 years ago seem to me now?