Prelude # 11 from 12 Preludes for Solo Guitar by Ken Hatfield

Prelude # 11 from

12 Preludes

for Solo Guitar

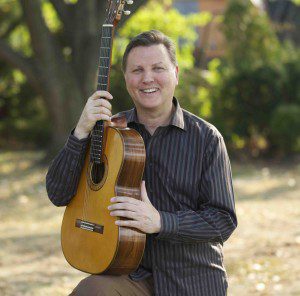

by Ken Hatfield

There are so many aspects involved in the creation and construction of any piece of music, that most great music cannot be entirely perceived and/or comprehended in one listening. For any music to communicate, the performer must understand it, then perform it accordingly, and the audience must listen attentively. (Often, repeated listens are required, a requisite not easily accommodated in our instant-access-to-everything-on-demand, short-attention-span world). So, as with all forms of communication, musical comprehension requires both attention and intention from all the parties involved. It’s not the purpose of these guitar tips to address the audience’s role in such communications, so I’ll limit the focus of my observations to aspects of form and content pertaining to Prelude # 11, the awareness of which may be helpful to the performer.

While the additional information the printed score provides can facilitate more understanding than listening alone, the mere act of playing a piece of music doesn’t necessarily guarantee insight. It is only when knowledge combines with interpretive insights that a multi-layered composition communicates on the many levels (for example, emotionally and intellectually) that it is intended to engender.

Link to Prelude # 11 on SoundCloud here: https://soundcloud.com/ken-

Prelude # 11 has at its core a very old musical concept: the preparation and resolution of dissonance. For anyone that has studied counterpoint, you know what I’m referring to. You can probably hear and can certainly see it throughout Prelude # 11. For those unfamiliar with the concepts behind these traditional compositional tools, it can be difficult to explain or demonstrate concisely how a dissonance is prepared and then resolved, because we now accept so many sounds as, if not pleasing, at least tolerable—sounds that would have been considered DISSONANT when these practices first evolved—that there is little or no consensus regarding what is or is not considered dissonant today. All of this can make these concepts seem antiquated at best or unfathomable at worst for many today. While a literal interpretation of what is dissonant and what is consonant may be passé, its fundamental truth and its application used to create the tension and release characteristic of our music is not obsolete, as I hope Prelude # 11 demonstrates.

If you’ve never studied the basic concepts of consonance and dissonance, I strongly encourage you to do so. If you have a rudimentary understanding of harmony as embodied in the chord tones of diatonic chords (and if you’re playing the guitar, you should have this basic knowledge), then the CliffsNotes/one sentence version of an explanation is: any note outside of the basic chord tones (generally the “passing tones” between the chord tones occurring in any tonality) can be dissonant and therefore will long for resolution. There are some that believe this is where the true emotion in all music originates.

The basic point is: given that all our “chords” originated as diatonic structures constructed in thirds (in root position closed), and are derived from scales, which themselves were derived from the overtone series of the single tone (generally the tonic or root of the key a piece of music is in), the discoverers of these phenomena considered them to be governed by laws similar to the laws of nature. Whether this is true or not is irrelevant to understanding how these tools came in to common usage and why they are still useful.

The reason the tones between the root, the third and the fifth of each diatonic chord are called passing tones is because they pass between chord tones in all scale structures. This makes perfect sense if you consider that between the thirds of each diatonic chord’s notes there is room for one note (in most Major and minor scales). This should be obvious, given that the distance between all scale tones for most scales is some kind of second (generally a Major or a minor second; even for exceptions like the Harmonic minor scale, most theorists consider the distance between the b6 and ∆7 to be an augmented second, not a minor third). So basically every scale can be heard as a series of alternating consonances and dissonances, with the relative function of the respective tones being interpreted in relation to the given chord upon which any note is sounded at any time. The notes that are functioning as a dissonance long for resolution to a note whose harmonic function is consonant. Now all of this occurs as the chords change, meaning the harmonic function of the notes keeps changing. So a note that was dissonant one instant may be consonant the next, and vice versa. This brings me to the teaching mantra I mentioned in a previous guitar tip: Context determines function!

Now that I’ve thoroughly confused you with my attempt at simplifying things, let me use examples from Prelude # 11 to illustrate what I am trying to explain.

Throughout Prelude # 11 textbook demonstrations of the concepts of preparation and resolution of dissonance occur. For example, the prime theme, which begins things in bar 1, contains a Bb Major chord with the 9th (considered a dissonance in traditional use) in the melody or top voice. This note (C♮) resolves down to a consonance, the root of the chord occurring in bar 1 (B♭). The guidelines (especially for counterpoint) once specified that a dissonance should be either prepared (though it is not prepared here, which I’ll explain later) or arrived at in stepwise fashion. And once the dissonance occurs it should be resolved in stepwise fashion. Because I wanted to begin this prelude with a note that illustrated what was once universally considered a dissonance, but is not heard that way today by most folks, I chose not to prepare it, but I did resolve it quickly and in stepwise fashion downward. This illustrates that the guidelines are malleable, but only if you have comprehension and mastery of them. Otherwise you’re operating out of lack of knowledge . . . a condition some call ignorance 🙂

Almost every one of the sections within the form of Prelude # 11 is built upon a dance between dissonance and consonance. Sometimes the dissonance is unprepared (as in bar 1); sometimes it is arrived at via stepwise motion (as in bar 2). Sometimes the dissonance resolves up (as in bar 4); sometimes it resolves down (as in bar 3). When they occur, these dissonances are generally in the top voice functioning in the role of the melody. But there are occasions when they occur in the middle voices, like in the first and second endings (where they are in the alto voice in bars 15 and 16, and again in bars 17 and 18).

In fact, the only section within this prelude’s form that is not based upon this interplay between dissonance and its resolution into consonance is the section comprised of sixteen bars occurring between measures 51 and 66. This is done for the purpose of contrast.

The germ/idea that gave rise to this composition is personal to me. The emotion I personally attach to that germ gave rise to the initial phrase that yielded the entire prelude, almost like an improvisation. The emotion that this dance between dissonance and consonance can still trigger in me when I play or hear this prelude is real for me. I do not expect it to trigger the same reaction for anyone else. But I do know that the way the performer addresses this interplay between consonance and dissonance is the key to finding one’s own way to make this prelude communicate what you want it to say when you perform it. At least for those that listen attentively.

The first sixteen bars of Prelude # 11 are the main theme. This section repeats and even changes keys in truncated form (measures 67 through 74 where it is in the key of C Major, not Bb Major). This primary thematic material is contrasted in two sections: (1) measures 19 through 34, where I contrast tonalities and keys while still using consonance and dissonance as the prelude’s protagonists; and (2) the aforementioned measures 51 through 66, where I move from Major to minor and abandon the consonance-dissonance interplay as the prime mover of the melodic narrative, using this section to set up the return of the theme in a new key, in shortened form. This modulated version of the theme brings us to a truncated version of our first contrasting section (a letter B of sorts, if you will allow a loose interpretation of formal considerations), which in turn brings us to our recapitulation (measures 83 through 98) with a two-bar ending in which the same dissonance we began with is unresolved (bar 99), while another is resolved (the subdominant minor chords eb–∆7 to eb–6 on beat one in bar 100), concluding on what is a modern (modern from the perspective of harmonic acceptance of what was once considered dissonant) chord: B♭∆ 7,9 (on beat 2 of the final bar). It is no coincidence that this final chord contains more vertical harmonic information than any other chord in the entire prelude.